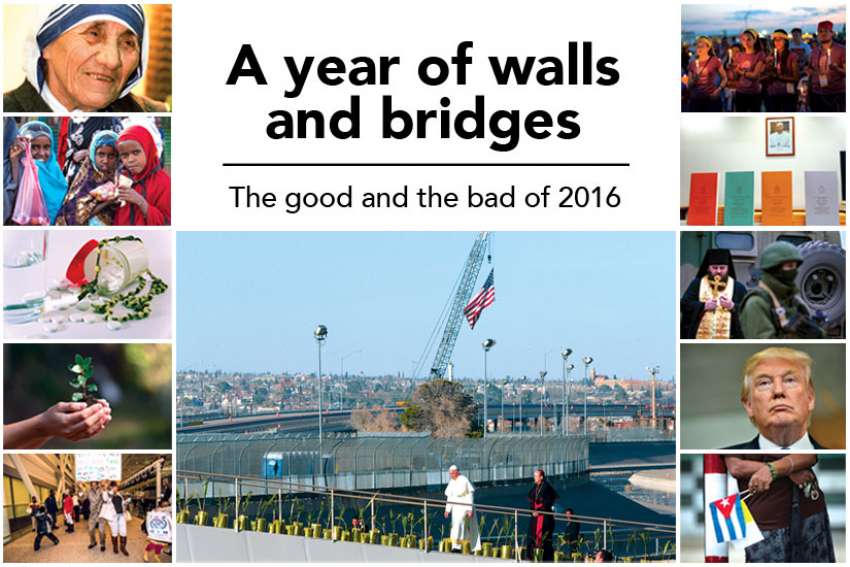

“A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian. This is not the Gospel,” the Pope told a planeload of journalists on Feb. 18.

“The founding fathers (of the European Union) were heralds of peace and prophets of the future. Today, more than ever, their vision inspires us to build bridges and tear down walls,” Francis told European politicians in Aachen, Germany, as he accepted the International Charlemagne Prize May 6.

“Do you know the first bridge that has to be built? It is a bridge that we can build here and now by reaching out and taking each others’ hands. This is a great bridge of brotherhood,” he told hundreds of thousands of young Catholics at World Youth Day in Krakow, Poland, July 31.

“Wherever there is a wall, there is a closed heart. We need bridges, not walls!” the Pope declared to the St. Peter’s Square crowd in his Nov. 9 Angelus address.

The plane-ride comment to journalists about bridges and walls received the most attention. Reporters had asked Francis to comment on Donald Trump’s election campaign promise to build a wall across the 3,201-km United States-Mexico border. The Pope first warned the journalists that he does not weigh-in on the politics of elections in any country, then gave into temptation to make his simple, common-sense observation about something more fundamental than Trump’s election rhetoric.

Trump also gave into temptation when he decided to take offence at the Pope’s remarks, claiming that one day the Vatican will need Donald Trump to defend the Holy See against an Islamic State invasion and then calling the comments of the spiritual father of more than a billion Catholics “disgraceful.”

It may be that the 80-year-old Pope sees something about our world and our times that calls for our attention. That was underscored by his designation of 2016 as a Jubilee Year of Mercy. Walls and bridges may be the key to any faithful understanding of 2016.

In Canada, a bridge of care which should carry us from this life to the next has collapsed under abstract legal and political arguments. Out of the rubble, citizens have been offered a legal right to have a medical professional end their lives.

Thousands of young people gathered in Krakow, Poland, in July for World Youth Day. (CNS Photo)

Thousands of young people gathered in Krakow, Poland, in July for World Youth Day. (CNS Photo)

Assisted suicide and euthanasia became legal in 2015 when the Supreme Court ruled the Criminal Code could not prevent people from seeking and finding a medicalized version of suicide. But it took until June this year for Parliament to pass a law.

As debate unspooled from the court ruling to the new legislation to permit an assisted death in restricted circumstances, Toronto’s Cardinal Thomas Collins was left pleading for honest, direct and simple language.

“The now officially accepted terminology, such as ‘Medical Assistance In Dying,’ does not describe medical assistance in dying,” Collins said June 20. “It describes killing. Let us say what we mean and mean what we say.”

The problem now is that the right to suicide in a medical setting is generating demands that it be mandatory for somebody to provide the service. Will this obligation be imposed on individual doctors? On the medical profession as a whole? On institutions, including Catholic hospitals, nursing homes and hospices? There are many unanswered questions and Catholics, including many doctors and nurses, find themselves stranded in the debate.

The work of building bridges is never done. Collins and other bishops reached out across religious divides to lobby for more meaningful ways to care for the dying, whatever the law may say about assisted suicide.

“Our traditions instruct that there is meaning and purpose in supporting people at the end of life,” said a June 14 joint statement from Christian, Jewish and Muslim leaders. “Visiting those who are sick, and caring for those who are dying, are core tenets of our respective faiths and reflect our shared values as Canadians. Compassion is a foundational element of Canadian identity, and it is accordingly incumbent on our elected officials at all levels of government to support a robust, well-resourced, national palliative care strategy.”

They argued there is no meaningful choice in end-of-life care if palliative care is only available to one-third of Canadians.

Hopes rest on a Conservative private member’s bill which would require the government to draw up a national plan to provide universal access to palliative care. Private members’ bills are rarely made law, but all three parties spoke in favour of Bill C-277 and it could be given the House of Commons thumbs-up by February.

The Catholic Organization for Life and Family repeated its plea for palliative care by reminding politicians that caring for the frail and the dying is one of those things that makes us human.

“The simple humanity of (palliative care) touches them and comforts them, as they experience respect for their bodies and for their human dignity at a moment of great fragility and vulnerability,” wrote outgoing COLF executive director Michele Bouvla in a letter to Parliament Dec. 8.

Pope Francis greets Syrian refugees he took back from Greece in Rome in April. (CNS photo)

Pope Francis greets Syrian refugees he took back from Greece in Rome in April. (CNS photo)

Nationally, Canadians have maintained a bridge to the suffering refugees of Syria. What began as a promise in 2015 to bring 25,000 Syrian refugees to Canada has grown to 36,393 as of Dec. 4. Catholic parishes continue to respond generously through the private sponsorship program, despite bureaucratic slowdowns since the government reached its promised number at the end of February.

The slowdown has exasperated many parishes and annoyed Canada’s bishops.

However, the problems of genocide in the Middle East, which threatens to wipe out ancient Christian, Yazidi and other minority populations, won’t be solved by resettling a few thousand refugees. The Catholic Near East Welfare Association of Canada, the Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace, the Jesuit Refugee Service and Aid to the Church in Need Canada continue to raise money and deliver programs to support refugees who hope to rebuild their communities.

Development and Peace helped design and took part in a global Caritas response to the crisis in war-torn Syria — a response that Pope Francis helped launch in July.

“It is unacceptable that so many defenceless persons — among them many small children — must pay the price for conflict, for the closure of the hearts and the want of a will for peace among the powerful,” the Pope said.

By December, Aleppo had fallen and the United Nations called it a “meltdown of humanity.”

Building bridges is a delicate business. Pope Francis found himself alone on something akin to a tightrope in February when he tried to extend the hand of ecumenical brotherhood to Moscow Patriarch Kirill. A brief meeting between the Patriarch of Rome and the Patriarch of Moscow at Havana’s José Marti International Airport Feb. 12 resulted in an agreement between two pastors to protect Christians in a world that had just witnessed the kidnapping and beheading of 21 Coptic Christians in Libya.

Pope Francis’ bridge building instincts went both directions across the historical divisions within Christ’s Church. His move toward healing the divisions of 1054 with the Orthodox were matched by a commitment to overcome the Protestant split in the Western Church which now enters its 500th year.

The Pope travelled to the Lund Cathedral in Sweden Oct. 31 to commemorate 500 years since Lutheranism forged a path apart from Rome. There he spoke of both sides in the Reformation divide upholding “the true faith.” He also pledged that Catholics and Lutherans, who both affirm a belief in the real presence during the sacrament of the Eucharist, will continue to work toward a common reception of communion.

Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople may have even had the last (meaningful) word in a Catholic fight that threatened to get ugly as 2016 came to a close. Pope Francis had released Amoris Laetitia (The Joy of Love), his apostolic exhortation on family life, in April to a generally favourable reception. However, there was backlash within the conservative Vatican ranks.

Beginning with a “dubia” mailed into the Pope in September, followed by a series of press interviews and the public release of their questions for Pope Francis in November, four cardinals demanded Pope Francis “clarify” his teaching on pastoral care for divorced and remarried Catholics in Amoris Laetitia — with American Cardinal Raymond Burke even threatening the pontiff with a “formal act of correction.”

Cardinals Lorenzo Baldisseri and Christoph Schonborn hold a copy of Francis’ apostolic exhortation on the family, ‘Amoris Laetitia.’ (CNS photo)

Cardinals Lorenzo Baldisseri and Christoph Schonborn hold a copy of Francis’ apostolic exhortation on the family, ‘Amoris Laetitia.’ (CNS photo)

The Patriarch of Constantinople sat down to read the 264 pages of Pope Francis’ reflections on two synods concerning marriage and the family, then wrote for the Dec. 2 edition of L’Osservatore Romano that the Patriarch of Rome has something more fundamental than legal procedures in mind.

Amoris Laetitia “first and foremost recalls the mercy and compassion of God and not just moral norms and canonical rules,” Bartholomew wrote.

Around the world in 2016, democracy has yielded frightening results. In March, a divided England voted itself out of the European Union, turning its back on an organization it helped found and encourage in the wake of the Second World War. In May, Filipinos elected a president who encouraged citizens to murder people they suspect of selling or using drugs. In August, a partisan and compromised congress removed Brazil’s democratically elected President Dilma Roussef.

Beginning July 16, the democratically elected government of Turkey pounced on a bungled coup attempt to suspend Turkey’s constitution and began jailing and firing hundreds of thousands of supposed enemies — mainly teachers and civil servants. By November, Americans were in no mood for civil debate. They elected as president a bombastic real estate magnate whose late-night tweets have included, “This election is a total sham and a travesty. We are not a democracy!”

At a Protestant campaign event, Trump justified not asking God for forgiveness by talking about his participation in the Eucharist in his Presbyterian church.

“When I drink my little wine — which is about the only wine I drink — and have my little cracker, I guess that is a form of asking for forgiveness, and I do that as often as possible because I feel cleansed,” he said. “I think in terms of ‘let’s go on and let’s make it right.’ ”

Pushed to a crisis, the world could still manage to come together. In March, the Earth’s atmosphere reached a tipping point — 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the air we breathe. Scientists peg the safe level at 350 ppm. On April 22 a record number of nations, including Canada, signed the Paris Agreement which commits them to action on climate change. As of December, 117 nations have ratified the agreement.

In September, the world was witness to the canonization of Mother Teresa, who personified the power the mercy with her work among the poor.

After the Year of Mercy came to a close in November, perhaps the one thing Catholics discovered is how much we need mercy.

“The mercy of God is not an abstract idea, but a concrete reality with which he reveals his love as of that of a father or a mother, moved to the very depths out of love for their child,” Pope Francis told us as he opened the extraordinary jubilee.

“God has no memory of sin,” he said as he closed the Holy Doors at St. Peter’s Nov. 20.