That’s the conclusion drawn from new research by Pew Research Center in the United States as part of its worldwide study of education among religious groups.

The average Canadian Christian has managed 12.7 years of schooling, compared to 13.1 years for Canadian Hindus, 13.3 for the religiously unaffiliated, 13.5 for Muslims and 14.3 for Canadian Jews. Only Buddhists, who come in at an average of 11.4 years of schooling, trail the Christian population in Canada.

Catholics make up 60 per cent of Canadian Christians, who in turn account for 67.2 per cent of Canadians.

The relatively modest level of schooling for Canadian Christians doesn’t come as a surprise to St. Jerome’s and Waterloo University sociologist of religion David Seljak. Age and immigration explain most of the differences, Seljak told The Catholic Register in an email.

“Immigrants tend to be better educated than the Canadian average since the point system filters out the under-educated,” Seljak said.

Not only are Canadian non-Christians more likely to be immigrants, they also tend to be younger.

“Christians tend to be older than the rest of the population and older age cohorts tend to have a lower educational achievement than younger Canadians, especially in Quebec,” said Seljak.

The average Canadian, regardless of religion, gets 12.8 years of schooling — 12.9 years for men and 12.8 years for women.

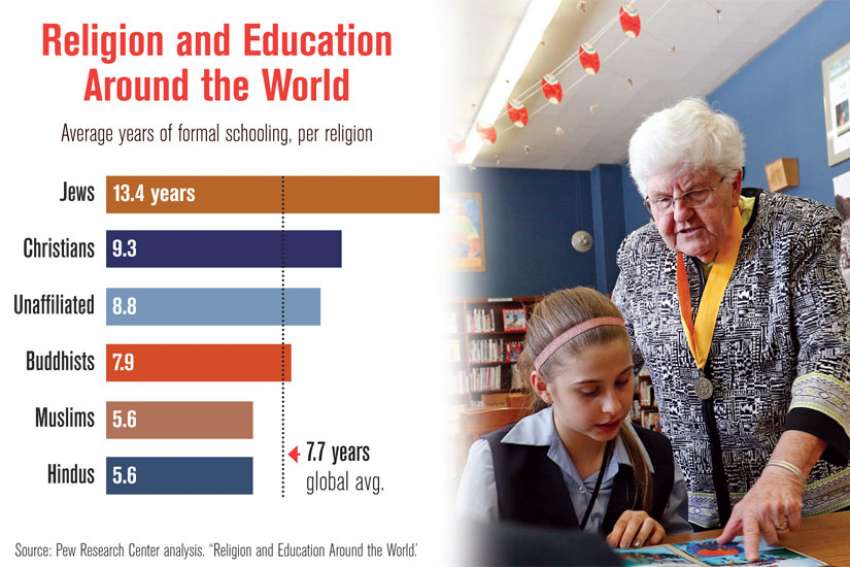

Canada’s numbers stand in contrast to the Pew Research data for education and religion globally. Worldwide, Christians average 9.3 years of education — the most of any group except the Jews, who globally come in at an average of 13.4 years of education.

Canada’s Muslims are exceedingly well educated with more than double the global average of 5.6 years of education for the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims. The same is true for Canadian Hindus, whose average of 13.1 years of schooling stands in contrast with the global average of 5.6 years for the world’s 1 billion Hindus.

Seljak noted that although Indigenous Canadians are less than five per cent of our population, they also have much lower education levels and very heavily identify as Christian,

Two-thirds of aboriginal Canadians are Christian, including about 40 per cent who are Catholic.

On average, federal government funding for education on reserves is 30-per-cent less than funding for provincial public schools. Combined with the legacy of residential schools, poverty and other challenges, education levels among Canadian aboriginals lag significantly.

Statistics Canada reported in September that less than half of Canadian aboriginals (48.8 per cent) had some form of post-secondary qualification, compared to almost two-thirds (64.7 per cent) of non-aboriginal Canadians between the ages of 25 and 64. Where less than 10 per cent of aboriginals (9.6 per cent) have a university degree, 26.5 per cent of working-age non-aboriginal Canadians hold a degree.

Higher education levels for Canadian Jews has a long history. Japanese and Jewish Canadians have for some time come out on top of education surveys “because they are both long-established ethnic communities with a strong emphasis on education and upward mobility,” said Seljak.

The relatively poor educational levels for Buddhists has a lot to do with Canada’s immigration history as well.

“Many of them were admitted as refugees from Cambodia, Vietnam and Tibet. Hence, the points-system bias in favour of the highly educated did not filter them out,” Seljak said.

Long established Chinese-Canadians who endured the head tax and years of racist exclusion were often prevented from assimilating and therefore remained in working class jobs and running small businesses, roles that didn’t demand much formal education.

The most complex picture is around the category most sociologists call “religious nones” — those who do not identify with any religion.

The nones include many immigrants from communist and post-communist societies in Eastern Europe and China. Their higher education levels are best explained by their immigration status, according to Seljak. Other nones are people of relatively high socio-economic status who are both better educated and more individualistic.