It seems unfair that we have to leave behind family, friends and the enjoyment of earthly life, often long before we are ready to do so. Resentment and questioning might bubble to the surface of our minds: did God shortchange us? Was there some mistake in the way humanity was designed? If God is omnipotent, why were we not granted longer lives?

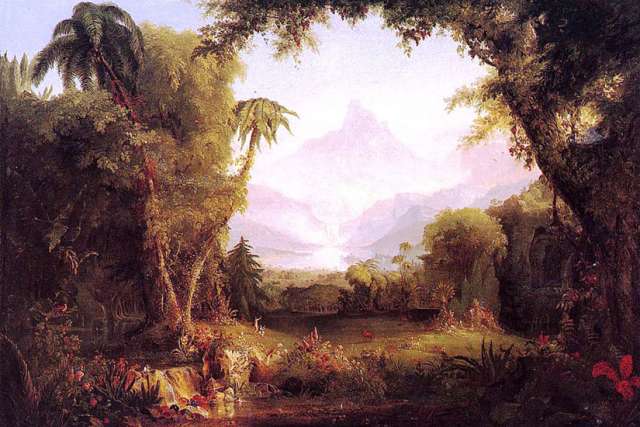

Wisdom has some surprising answers. Since God is only about life and goodness, creation itself is unequivocally good. There is nothing in the created order that is intrinsically evil, death-dealing or negative. Not only that, God’s plan for us was immortality and incorruption, even sharing in God’s image of eternity.

So what happened? How did we get sidetracked? The author of Wisdom refused to lay the responsibility on God’s doorstep, but blamed the devil and by implication humanity itself. Death, pain and negativity are not and never have been part of God’s nature or plans. Being out of harmony with God brought these things upon us. As the story goes, humanity had to take the long, hard way back to this intended state. This involved thousands of years of salvation history, much struggle, and ultimately the life, death and resurrection of Jesus.

Or was that actually part of the original plan? The “happy fault” and “necessary sin of Adam” sung at the Easter vigil suggests that this may be the case. Our lives would be very different if we would focus on the compassionate, life-filled and life-giving God rather than on our fears of death. Death is but a passage; God has far grander plans in store for us, but it is a long process.

Paul was the consummate fundraiser. He used flattery, a bit of guilt, an appeal to the example of Jesus and finally invoked a sense of fairness to convince the Corinthian community to donate to the collection for the Jerusalem church. They are all good arguments, but not just for fundraising. It offends decency and the divine teachings for some to have too much and others too little. A more just and equitable society and world is not about charity but what is right. It’s a very simple but very telling argument.

The two miracles of Jesus also suggest that our attitudes influence our experience of illness and death. The woman with the flow of blood had probably experienced the ostracism that accompanied the stigma of being impure. But she was convinced that if she could only touch Jesus’ clothes, she would be healed.

With great courage and persistence, she did so and Jesus immediately knew that power had gone out from Him to someone. As she confessed that she had been the one who touched Him, Jesus declared that it was her faith that enabled the healing to occur. There was nothing magic about His garments — it was her attitude of hope and trust in God.

His arrival at the home of the dying daughter of the synagogue official was too late. The funeral had started, along with grieving and wailing. Jesus had already told them not to fear but to have faith. Now He questioned the reason for their intense grief and informed them that the girl was merely sleeping.

These two statements must have seemed like idiotic nonsense to some and extreme insensitivity to others. In fact, they laughed at Him. We would not say similar things at a funeral — unless, of course, we were Jesus. By taking the little girl by the hand and commanding her to get up, Jesus restored life to her and proved once and for all that God is God of the living and not the dead.

Rather than blaming God or fate, perhaps we can take a collective look within ourselves. We help to create the world we experience. When humanity’s relationship with God is so conflicted and discordant, we should not be surprised to see that reflected in the natural order.