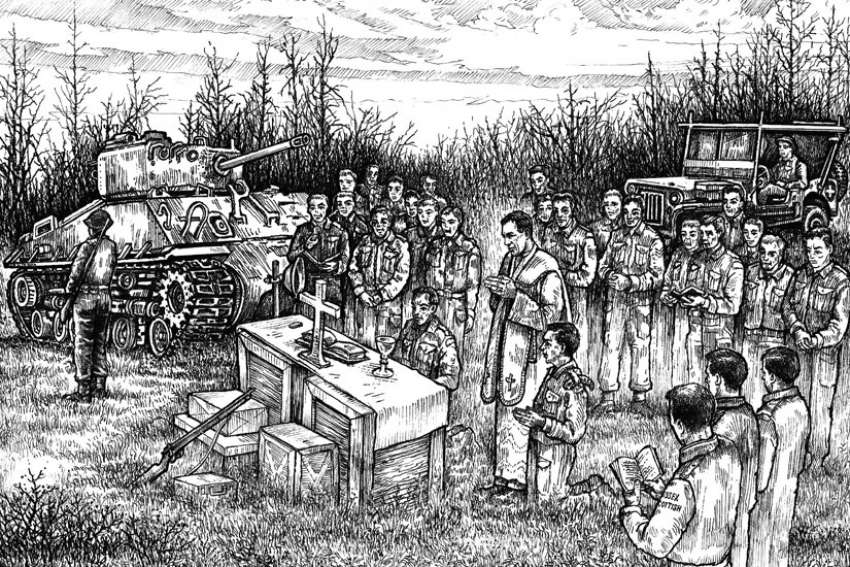

Rev. Major Mike DaltonMore than six years after his death (in April 2009, a month before his 107th birthday), his nephew Brian Dalton has self-published a book of Fr. Mike’s wartime reflections, The Padre’s War Diary. Brian, an artist and retired teacher, spent four and a half years collecting, editing and illustrating the diary, resulting in more than 300 entries and 200 illustrations.

Rev. Major Mike DaltonMore than six years after his death (in April 2009, a month before his 107th birthday), his nephew Brian Dalton has self-published a book of Fr. Mike’s wartime reflections, The Padre’s War Diary. Brian, an artist and retired teacher, spent four and a half years collecting, editing and illustrating the diary, resulting in more than 300 entries and 200 illustrations.

Fr. Mike was “one of the most influential men I have known,” said Brian, who remembers his uncle from childhood as a “source of fun and excitement.”

“Like all of us he had his flaws, but it was never boring when he was around.”

Born in Goderich, Ont., Fr. Mike was ordained in 1932 and he joined the Essex Scottish Regiment in Windsor in 1939.

During the war, Dalton served on the front lines in the bloody march across Europe, earning the prestigous Order of the British Empire, presented to him by King George VI. After the war, he continued to serve his church and community in southwestern Ontario with distinction until his death.

In 1967, he was the Royal Canadian Legion’s Veteran of the Year, and the city of London, Ont., later named a street after him.

“The Padre, in his emotional journey, confessed to a period of atheism, but returned to his faith,” Brian told The Register. “He liked the idea of the unity of all churches, but his devotion to Catholicism and Catholic principles was clear.”

In honour of Remembrance Day on Nov. 11, here are excerpts from the Padre’s diary from the months following the Canadians’ D-Day landings on Juno Beach in France.

July 8, 1944

First official act yesterday on French soil was to put ‘Ave Maria’ on gramophone. Also John McCormack singing ‘Say a Little Prayer.’ John answered my letter when I told him this. The continued thunder all day is artillery. No one is alarmed. All are anxious to do their duty to God and country. After Mass 500 men sang ‘Good Save The King’ and ‘Oh Canada.’ In liberated France it was a thrill.

July 12, 1944

Move to Casualty Clearing Post – 0900 hrs – terrific mortar fire blasts feel like hail in our orchard. One piece came in the back door of my truck and out the side one foot from where my feet were. I was too busy to be unduly alarmed as I rushed out to help a dying British Ack Ack gunner to recite: “Jesus mercy.”

I am now veteran enough to move into a slit trench even though it is too noisy to sleep, it’s better than above ground. I got to sleep at 3 a.m. The first sleep in three nights. Our own artillery keeps us all awake.

July 13, 1944

Advanced dressing Station near Caen. Three non-Catholic stretcher bearers, McGregor, Bond and Quigley pray the “Our Father” with me in the trench. In spite of intense artillery fire and shrapnel falling all around, one of them had to go out before dawn and pick up some wounded, and he did it.

July 18, 1944

“My God it’s Patterson.” I could tell by the pale face in the jeep that he was dead. Then I said to the Military Police: “Patterson’s brother is the Adjutant to the Colonel in R.Reg.C. May I go up and tell him his young brother is dead?” He gave me an armored car and chauffeur and I found Adjutant Patterson sitting on the grass checking up on the casualties (no place else to do it). When I told him the sad news, he cried and said: “I promised our parents I would look after him.”

July 18 (later), 1944

Anglican Chaplain Harold Appleyard was at prayer — Last Rites in biggest mass burial I saw since Dieppe. Canadians and Germans — dozens of them in the sun. Here as in the ruins of Liseaux, human flesh smell is depressing. The future Bishop Appleyard came back with Patterson and me when I asked him to bury Patterson’s brother. I shouldn’t have asked him for he was exhausted, but calm.

July 19, 1944

Louvigny. This “Holding Area” designated by Montgomery to be just that — “to hold like a puppy to a root.” In this town a happy smiling Lieut. Wm. Patterson brought us Lieut. Bud Lynch, saying to me “Padre look after Bud he has a bad wound.” Bud, with a mangled arm, brought back prisoners. He often read the Mass in English for me. Bud said: “Rub my hand Padre,” but the circulation was failing and he was jeeped to field hospital and his arm was amputated.

July 22-24, 1944

All come to Mass and Communion in a damp cold cave inhabited by evacuees of Caen. (30 ft. under rock) French sang beautifully. Mass again in caves at Fleury-sur Orne.

July 24, 1944

I remained with 21 F.D.S. a few days and nights in the cave. Dampness in cave has been here since William the Conqueror, soon after 1066, hued out stone for the great Cathedrals of England. 300 casualties came through in nine hours during fierce night battle. I helped stretcher bearers carry them from jeeps. Buried several within. Many died from shrapnel fire. My name was printed on a little white cross, by error. Pall bearers ducked once, but recovered their balance.

July 25, 1944

At one Mass I turned to give last blessing and not one soldier was in sights. They all had ducked into the trenches.

July 26, 1944

Mass in mill surrounded by tons of wheat. So far I have not had to interrupt Mass due to shelling, but plenty heard close by. The Mass brings at least half hour respite from mortar fire. Earlier at a Mass I broke the rule of “No collections at Mass.” The lads gave thousands of francs. The Pastor was joyful. I should have asked for a second collection.

Awakened at 6 o’clock to bury a dead German. (They assured me he was dead.) I went to a majestic German tank they had towed back. I said “Produce your corpse.” They couldn’t. His feet were locked at the controls – they asked for a saw.

Aug. 17, 1944

On move again through Bretteville towards Falaise. Rocquancourt a mess. Allied gap closing south of Falaise. Germans outwarred again. Found church not too badly shelled. Louis will clear broken masonry off what was a beautiful altar, and men will attend Mass amid the ruins. Sometimes I hide chalices from looting sacrilegious soldiers.

Sept. 2, 1944. Dieppe

I said Mass at Cdn. Cemetery where 854 allied lie buried since August 19, 1942. All Regiments of Bde. Attended and received Communion as they knelt on graves of their fallen comrades. Many old friends’ graves were recognized. 539 Essex Scottish, including 28 officers attacked Dieppe. 44 returned – no officers. That was when I was made Colonel for a day.

Sept. 5, 1944

I slept in a Dieppe Convent that the Germans had used previously and later returned to the Sisters. I felt guilty the morning I awoke and learned that I slept in the very bed that German General Rommel had used for many months during the heat of the War.

Sept. 13, 1944

Flanders charming and hospitable – on wheels again across border into France near Dunkirk. Boys are lonesome leaving friendly Belgians. Belgian horses are masterpieces of equine pulchritude and beauty and strength. The lads say the same thing about the women. “Get up, horses is me hobby” said I to the lad who said to his two-minute acquaintance: “we’ll have to make love fast. We only have a short stay.” Some are serious and want to get married. I saved a few marriages.

Oct. 16, 1944

Sergeant Art Chart was an Essex Scottish lad who came to R.H.L.I. during Confession. He told me his platoon couldn’t attend Mass as they may have orders to fire anytime. He inquired: “Can you bring Confession to our gun position?” I replied: “If H.Q. will allow it.” He was wet, so was I. It was dusk then and it would take us several hours to travel back ver strange roads with detours.

I consecrated extra Hosts and started off on foot as H.Q. might stop me if they saw the truck. After some searching and hollering I found them. Their mortar guns appeared in the moonlight temporarily covered from the rain. I stood to hear their Confessions. It was a tense moment as they recited the Confiteor (I confess). Then the prayer of the Roman Centurion to our Lord: “Domine nun sum dignus” (Lord I am not worthy.).

Among some of the men who received Communion, I remember the faces in the light of the oil lamp of Art and Jim Caba – a youth I had prepared for Confirmation in “Tin Can City” in south Windsor, and a lad Moriarty.

That was Art Charette’s last Communion. Next morning a few few hours later he fell in honoured glory. Do you blame me for bypassing H.Q. after such a demand? While he was in England his wife died leaving an infant son. Often at night in Maida Barracks, he would call at my billet and discuss the future of his son and heir. I now have some definite facts to comfort his next of kin.

(The Padre’s War Diary, based on the personal World War II War diary of Rev. Major Mike Dalton, is edited and illustrated by Brian Dalton. For inquiries about the book, email rbdalton@bmts.com. For more about the artist, watch this video)