Examples are on display at Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario until Jan. 22.

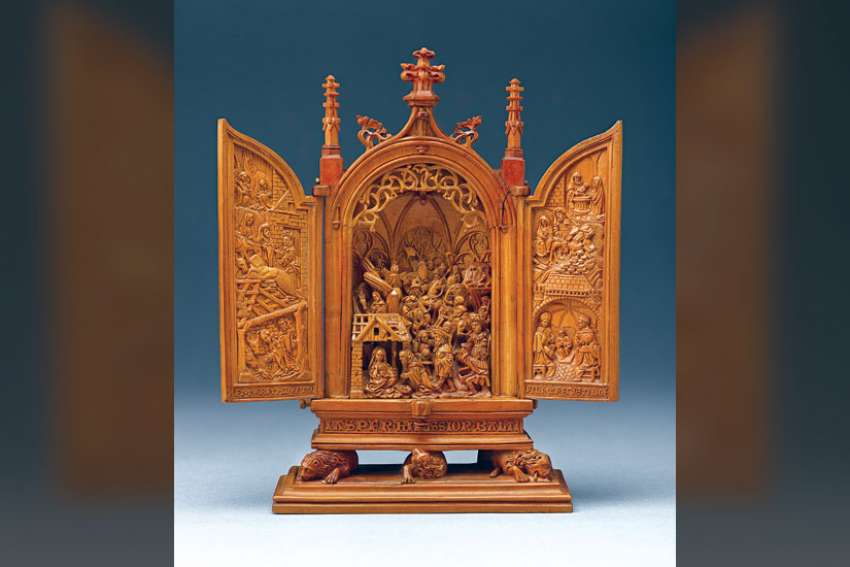

The Small Wonders exhibition gathers together awesome (in the sense of inspiring awe) miniature boxwood sculptures — finely crafted objects of devotion that unveil the holy in an alternate universe which can be held in the palm of your hand.

Included are a couple of nativity scenes carved in exquisite, mesmerizing detail. They show how Christian devotion to the Christmas story has remained constant over the centuries.

The anonymous artists who crafted miniature rosaries, prayer beads and altarpieces on display in the Small Wonders exhibit were responding to a new, richer, more secular, more sophisticated Europe which emerged out of the high Middle Ages, said AGO curator Sasha Suda.

“You have people who, in spite of a more secular way of life, are certainly Christians and believers,” Suda told The Catholic Register. “They have a strong investment in their faith and want to have a piece of the Church on hand to have those moments of contemplation and devotion.”

Such individualism was inconceivable when Europe was poor, backward and devastated by the Black Death. From the fall of Rome (between 410 and 530) until the rise of the new merchant class (1300s), just about the only way to become more spiritually connected was to join a monastery. Which is to say, medieval spirituality was a collective enterprise.

Beginning with the devotio moderna movement in the 14th century, lay people began to explore their personal spiritual lives. This led to a rise in personalized prayer books and manuscripts. Personal objects of contemplation, such as the boxwood miniatures, were the next logical step.

“On the one hand, they are luxury objects that meet the standards of the heights of fashion,” said Suda, “while really encouraging contemplation and devotion of the highest order as well.”

The Christmas scenes show how renaissance Christians were open to using the imagination to incorporate Gospel stories into their own lives. Miniature annunciation scenes showing the angel Gabriel telling Mary she will give birth are set in the here and now of wealthy northern Europeans in the 16th century.

“They’re very much a product of their contemporary context,” said Suda. “You have the annunciation to the virgin at the top which gives you the detail in a room, her room. You have this gorgeous canopy above her bed, she has a prayer book under her left hand. You have the cascading of the drapery of her dress and her hair again. So you have a little bit of a look into a contemporary bedroom with its tiled floor.”

To the 21st-century mind it might seem obvious that the Blessed Virgin Mary was not the rich young daughter of a wealthy Dutch merchant and nobody dressed in brocade or possessed personalized prayer books in Bethlehem under the reign of King Herod. But the point of the boxwood beads was to contemplate this essential moment in the history of salvation so it would be present and real to the owner of the prayer bead.

“People (in the 16th century) talk about being transported and having visions, going through a kind of devotion that is very centred away from the public experience, what they might even describe as the spectacle, of the liturgy,” said Suda.

To 16th-century eyes as much as to 21st-century gallery goers, there’s one essential mystery wrapped up in all the boxwood miniatures. The unfolding layers of intricate detail always inspire the question, “How did they do that?”

At the AGO, curators have gone to great lengths to unravel the mystery. Powerful medical scanners were employed to highlight every detail.

“We did a lot of this scanning of the objects and what we learned was that there are many objects (inside the beads) that were never meant to be seen but are fully realized in the carvings,” said Suda.

What was the point of carving something that is hidden behind another layer within the bead?

“The artist is realizing this thing fully, clearly thinking you have to believe in what you can’t see — just as in your faith,” Suda said. “You have to believe what you can’t see and believe that it’s real and it’s there. These are their own physical manifestations of that principle of their faith.”

The AGO show includes a 3D, virtual reality tour of a bead which contemplates the last judgment with scenes of Heaven and hell.

The three-dimensional renderings and explanations of how the prayer beads were constructed don’t explain everything, said Suda.

“I was worried that would take the mystery away. But the fact that we know now is really even more puzzling because — based on what we thought we knew about the 16th century and magnification and other technology available to the artists — then what we’ve discovered is impossible.”