Foster kids shut out from education grants

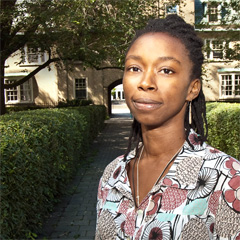

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register TORONTO - Aisha Aberdeen wasn’t born on third base, and she doesn’t imagine she hit a triple. But as the school year starts, the former foster child is ready to trot home.

TORONTO - Aisha Aberdeen wasn’t born on third base, and she doesn’t imagine she hit a triple. But as the school year starts, the former foster child is ready to trot home.Aberdeen has done what almost no kid who has been through foster care ever does. She’s graduated from the University of Toronto with a double major in forest conservation and Caribbean studies. Now she’s planning graduate studies in the forests of Kenya this year.

Fewer than 44 per cent of children who wind up in foster care complete high school before they’re 21. Only 20 per cent of those (8.8 per cent of the total) go on to any form of post-secondary education.

In the general population, 75 per cent of Ontario kids graduate from high school and 40 per cent continue their education past high school.

How did the 27-year-old mother manage to be the exception?

“I can’t say this is about anything but God,” Aberdeen said. “There’s a tendency for many of us in care to get forgotten.”

The forgetting extends to government policy, said Laidlaw Foundation executive director Nathan Gilbert. Three years ago the federal government made matching grants — the Canada Learning Bond — available to families who are saving up for their children’s education. Nobody seems to have considered what happens to children who don’t have parents capable of opening a Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP) to qualify for the government grants, said Gilbert.

“These are the kids who end up in persistent poverty,” said Gilbert.

It would cost about $8 million per year for the federal government to set up RESPs for the 18,000 Ontario children in foster care, according to the Laidlaw Foundation report “Not So Easy to Navigate.”

The Laidlaw Foundation funds youth programs in the neighbourhoods people avoid after nightfall and advocates for youth with governments. Making the Canada Learning Bond available to foster children and making sure the kids all have RESPs backing them up would do more than provide foster children with a little bit of money for education when they age-out of care at 18, said Gilbert.

“It’s about building aspirations, maybe even expectations,” he said.

Touted as a way to even the educational playing field for poor families when it was started in 2007, the Canada Learning Bond actually seems to be doing a better job of helping the middle class. In 2008 only 16 per cent of low-income families had taken advantage of the program.

Ottawa had budgeted for the program to cost $170 million in its first two years. Because of low take-up it actually cost less than $51 million and benefitted just 76,000 children.

An EKOS Research poll of 900 families making less than $38,000 a year in 2008 found only one-third had ever heard of the Canada Education Savings Grants and only one in 10 knew anything about the Canada Learning Bond.

Gilbert plans to ask Ontario Minister of Children and Youth Services Laurel Broten to push her federal counterparts to fund Canada Learning Bonds ($500 to start, plus $100 each year) for all foster children. He has a meeting scheduled with the Minister on Sept. 8.

“The idea that they would have a nest egg to support their life chances is, we think, an important one,” Gilbert said.

Aberdeen dropped out of high school at 16, after a year in foster care. She then lived on her own through a succession of dead-end jobs and her fair share of trouble until she turned 21. She knows she could have fallen into the statistical norm of foster kids who fail to get an education and then fail to ever extricate themselves from poverty.

“Between 16 and 21 you can really lose your life — all sense of direction,” she said.

Aberdeen knows she had to fight against expectations most people had for her — a black kid with a thick Trinidadian accent who came from a neighbourhood too much in the news. At 21, she enrolled in the University of Toronto’s advanced placement program for adult students who never finished high school.

She got through that and into her first year of university before she was pregnant and diagnosed with lupus. Through that difficult pregnancy, she kept going to class. Now her three-year-old daughter Kenya is her inspiration to do even more.

Expecting every foster child to buck the kind of odds that Aberdeen faced is no kind of national policy, said Mary Bowyer, executive director of the Toronto Catholic Children’s Aid Society’s Hope For Children Foundation.

“What we have to do is look at how we can bring youth in care up to the level of the average Ontario youth,” Bowyer said.

“By providing youth with an education we are providing them with the resources to break the cycle of poverty.” That’s tough to do when foster care kids lack support past the age of 18 that most kids take for granted, she said.

“It’s larger than the tuition costs. Kids have the cost of maintaining themselves in independent housing without the support of a family where they might be able to go for Sunday dinner, or to get their laundry done, or to get a care package of food when they’re broke,” said Bowyer.

The Hope For Children Foundation handed out more than $200,000 in scholarships to just over 100 former Catholic Children’s Aid Society kids at its annual Hart House dinner for graduating students Aug. 25 at the University of Toronto.

Please support The Catholic Register

Unlike many media companies, The Catholic Register has never charged readers for access to the news and information on our website. We want to keep our award-winning journalism as widely available as possible. But we need your help.

For more than 125 years, The Register has been a trusted source of faith-based journalism. By making even a small donation you help ensure our future as an important voice in the Catholic Church. If you support the mission of Catholic journalism, please donate today. Thank you.

DONATE