Whether you blame the mental health system, drug addiction or the absence of affordable housing, homeless psychiatric patients have become part of life in the big city.

Most of the debate over what to do about Toronto’s open-air insane asylum is a discussion about what governments should do — which programs government should fund, which governments should fund them and then how and where they should operate.

In almost 50 years of working and living with long-term psychiatric patients who have been either homeless or close to it, Fr. Joe MacDonald never gave much thought to what the government should be doing. The Capuchin Franciscan friar has been too busy doing what he can every day, making a home for psychiatric patients.

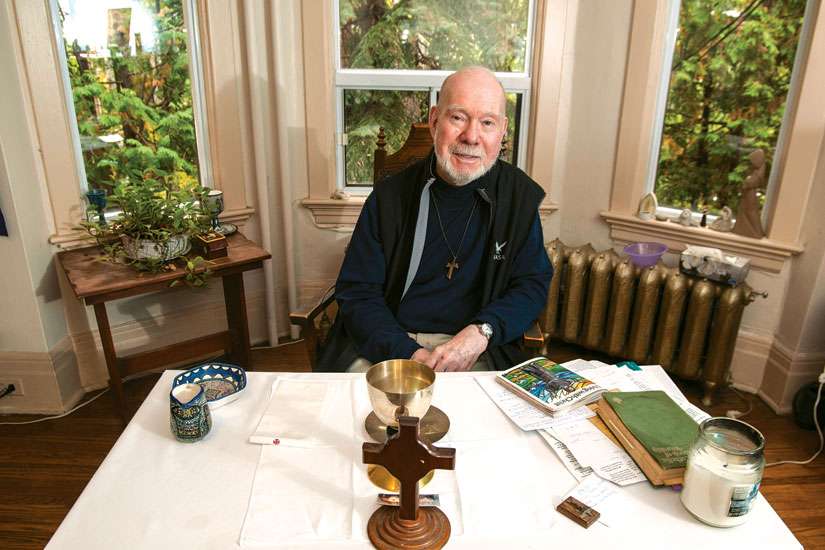

Eighty-one years old and living with Parkinson’s, MacDonald celebrated 50 years as a priest Oct. 23. He’s the founder, chaplain and chief driving force behind Poverello Charities Together, which houses and cares for 15 ex-psychiatric patients who live with MacDonald and three staff members in five linked houses in Toronto’s South Cabbagetown district.

“We never took a cent from the government,” said MacDonald. “From day one we have never taken funds from the government, although the government would offer it.”

MacDonald doesn’t just mean his present supportive housing arrangement for ex-psychiatric patients. Since 1968 when his superior sent him to live and work at the Good Shepherd Mission on Queen Street East, MacDonald has set up and run drop-in centres, shops where the poor can both work and buy things cheap and homes where people feel safe — all independent of government funding. The priest’s model for the Poverello homes has nothing to do with the latest research in psychiatric treatments or social work. MacDonald offers people the kind of community life Franciscans strive for among themselves.

That includes morning and evening prayer, prayer before meals and daily Mass. While not all the residents participate in the religious discipline of the community, and MacDonald would never force anyone to pray, it does provide a rhythm and structure to the days at Poverello.

MacDonald’s goals are higher than providing a refuge from life on the street. While he wouldn’t claim the experience of Christian community can cure mental illness, he believes the experience of Christ in community heals all.

“It’s a powerful thing, this Christianity. And we haven’t plumbed it at all. We skirt the surface. We pay lip service,” MacDonald said. “But no one really lays down his life for another. No one says, this is where it’s at. But when we do that, people change.”

Some of the people living at Poverello have been with MacDonald for 25 years, living as part of a community.

“They have lived fulfilled lives. They mightn’t have a nine-to-five job, but they live fulfilled lives.”

There is simply no doubt in the scientific literature on mental illness and homelessness that if people are given a secure place to live and a sense of belonging it has immense therapeutic benefit, said Steve Lurie, the executive director of the Canadian Mental Health Association — Toronto Branch.

There are about 10,000 people on waiting lists for supportive housing in Toronto and 5,000 more apply every year.

“Most of the evidence over the last 30 years says that people prefer to live in their own space, but with supports they decide they want,” Lurie said. “That can include wrapping a community around that.” The degree or intensity of community can vary, but community matters, said Lurie.

“Just putting people in a room where they are going to naturally isolate isn’t particularly effective,” he said.

Whatever form supportive housing takes — whether it conforms to the Franciscan Rule, the Benedictine Rule or runs on a secular basis — research shows “it’s actually cheaper than the alternative,” Lurie said.

For the most visible and troubling of the homeless and psychiatric population — the ones who are frequent visitors to hospital emergency rooms and often arrested — for every $2 spent on supportive housing the government saves $3. For the less visible population who because of mental illness have trouble remaining housed, for every $10 spent on supportive housing the government saves $7 in other health care and social service costs, requiring a $3 subsidy.

The Canadian Mental Health Association estimates it would cost each Canadian the price of six cups of Tim Hortons coffee per year over 10 years to get psychiatric patients properly housed — about $4.2 billion.

For MacDonald, it’s not about the money. It’s about commitment.

“I just think that we haven’t tried the Christian presence,” he said. “Most mental illness is chemistry, body chemistry that has to be adjusted to a degree. So you do need medical people and you do need a good listener, a social worker. But to depend on that and say it’s the only way would be a mistake. I don’t think there’s something wrong with the mental health system, but it just doesn’t go far enough. We think that our expertise is what matters. It’s our presence that is most healing.”

MacDonald knows that being present is not without cost.

“This whole idea of living with the poor as a priest, which I’ve done now for 47 years downtown, it’s not acceptable by the majority of priests or the majority of religious. It’s… well, we still have our security blanket and whatever else that we have,” he said. “Jesus didn’t zap home at night. He didn’t take off for the weekend or the long weekend. He didn’t have holidays. He threw away the key to His divinity and became one of us, absolutely and unconditionally. Until we do that in identifying with our brothers and sisters… I don’t see anything happening because we’re living the good life while they’re not. That tears them apart and it doesn’t do anything for us.”